Ketchup Pasta Sauce

Dinner was an array of mismatched ceramic ware, flanked by the rice cooker in the corner. It was a permanent fixture in the dining room that we never used, because even twenty steps from the stovetop felt too far removed from the food.

A hungry apology to my mother

We never microwaved.

Dinner was an array of mismatched ceramic ware, flanked by the rice cooker in the corner. It was a permanent fixture in the dining room that we never used, because even twenty steps from the stovetop felt too far removed from the food.

I was five when we started eating in the kitchen. Dinner consisted of a vegetable, a meat or two, rice, and soup. Instead of little mounds on individual plates, dinner was a big steaming heap of green bok choy sweating garlic slivers in their chicken broth sauna. Knuckly pork braised in red fermenty stew, bits of white cartilage peeking out from rib chunks that grew more translucent as they cooked. We ate around these bones with our teeth before spitting them out unceremoniously next to our rice bowls onto torn pieces of Bounty paper towel.

Only 58% of dinners eaten at home in American households in 2014 were homemade

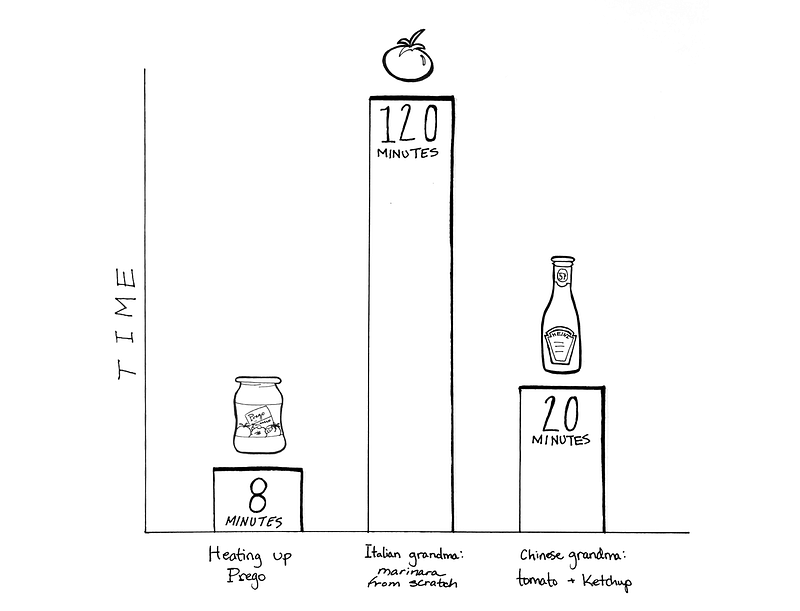

I didn’t make it easy for my mom. As a Cantonese kid growing up in suburban Pennsylvania, all I wanted for dinner was Pizza Hut. No mac and cheese? At least make a meatloaf! One time my grandmother gave in after I nagged her for weeks about spaghetti. She only had my description to go on, but she managed to conjure up a sauce from fresh tomatoes and ketchup. She couldn’t comprehend a meal of just pasta and red stuff so she worked in slow cooked onions to satisfy her sensibilities.

I yearned to eat like all the other kids.

I’m 33 now. I have a loving and supportive Other and kids seem to be a real and imminent possibility. I don’t own a biological clock; I have no idea when I’ll be ready. Hearing the gory details of carrying a would-be little person inside me still makes me question whether all mothers aren’t insane. But I’ve never had any misgivings on how I will raise my child around food.

I will cook for her every week, with my heart leaking into every bite. I will finally overcome this brown thumb that keeps killing tomato plants, so that Garden Fresh is not just a sign at the supermarket. I will slay the freshest sea bass from the live fish markets in Chinatown. I’m more excited than anyone should be about pureeing carrots and parsnips into baby food, and for the first time I try out pâté on her. What will she do?! Will she spit it out? I bet she’ll love it.

I’ve never had any misgivings on how I will raise my child around food.

I can’t wait to introduce her to thousand year old duck eggs, and fermented bean curd, and chicken feet — the cold freaky kind doused in vinegar and chilis. All the things that my mom made “normal” for me. I didn’t appreciate it when I was five but as I type this, 3,000 miles away from her cooking, I can‘t take back those times I coerced her into buying me McDonald’s happy meals. I wish I could replace every chicken nugget with just another bite of her pickled cabbage steamed pork.

I joined Josephine because it spoke to me about things I had just begun to understand. The power of food to bring people closer, a world where every meal we eat is a reminder from a real person that we’re loved. My “job” is one more puzzle piece— like the books on my nightstand, or devouring ‘Cooked’ on Netflix. The puzzle of how to create and protect this delicious cocoon of home-cooking for myself, and multiply it five-ten-hundredfold so that the McDonald’s of my youth will be a far cry from the homemade congees, and spaghetti marinaras for future generations. That is my work.

Many thanks to Ana Mason for illustrations.

This post originally appeared in The Dish, a blog from Josephine.